ENCW 452 SENIOR PORTFOLIO SEMINAR

Mar 14th, 2024 by JGB

Too Much Happiness

May 13th, 2024 by Grace Quintilian

The second of the Alice Munro stories that I have chosen to read this week is “Too Much Happiness.” Like “Runaway,” it is the titular story of the collection it was first published in. “Too Much Happiness” is a fictionalization of the life of Sophia Kovalevskaya, a famous seventeenth century Russian mathematician who died at only 41 years old. While the majority of the story is told in the form of flashbacks, the story technically only takes place in the final few weeks of Sophia’s life. In the very first scene, Sophia is walking in a cemetery with her fiance on New Year’s Day, and she remarks that “one of us will die this year” – a Russian superstition which she does not seem to take seriously, but which comes true in the end. Sophia takes an arduous trip to Stockholm, during which she catches pneumonia and quickly passes away. The flashbacks, on the other hand, recount the span of Sophia’s life, including her struggles as a woman mathematician, her relationships with her family, her first marriage to a husband who killed himself, and her relationship with her new fiance. Throughout, themes of the struggles of women during that time are deeply woven in.

The second of the Alice Munro stories that I have chosen to read this week is “Too Much Happiness.” Like “Runaway,” it is the titular story of the collection it was first published in. “Too Much Happiness” is a fictionalization of the life of Sophia Kovalevskaya, a famous seventeenth century Russian mathematician who died at only 41 years old. While the majority of the story is told in the form of flashbacks, the story technically only takes place in the final few weeks of Sophia’s life. In the very first scene, Sophia is walking in a cemetery with her fiance on New Year’s Day, and she remarks that “one of us will die this year” – a Russian superstition which she does not seem to take seriously, but which comes true in the end. Sophia takes an arduous trip to Stockholm, during which she catches pneumonia and quickly passes away. The flashbacks, on the other hand, recount the span of Sophia’s life, including her struggles as a woman mathematician, her relationships with her family, her first marriage to a husband who killed himself, and her relationship with her new fiance. Throughout, themes of the struggles of women during that time are deeply woven in.

Sophia was a woman who breaks many of the expectations placed on women of her time. She was married, but it was a “White Marriage” – a marriage done for legal purposes, to allow the woman freedom from her parents. She and her husband Vladimir did not live together, except for brief periods when it was convenient. Sophia had a daughter, Fufu, who she was often criticized by other people in her life for “neglecting” – she often left Fufu in the care of others while she pursued her career. Most prominently, Sophia was a mathematician. She was the first woman to obtain a doctorate in the field, and she was doubted every step of the way. Her doctoral advisor, Weierstrass, even doubted her when she first came to him, at first brushing her off by giving her a test he assumed she would fail, and then when she exceeded his expectation, the Munro states “But he suspected her still, thinking now that she must be presenting the work of someone else, perhaps a brother or lover who was in hiding for political reasons.” Even when he did come to accept her as his advisee, he still did not entirely respect her as a woman. This is illustrated in the following exchange:

“Truly I sometimes forget that you are a woman. I think of you as — as a —”

“As a what?”

“As a gift to me and to me alone.”

Sophia seems to be touched by this, but it is still misogyny. Later in the story, she observes that her (now deceased) husband had not had “the manly certainties,” and that this was why he was able to treat her with some level of equality but never “that enveloping warmth and safety.” This is to say that a man is either able to respect a woman or he is able to love her, but not both. Weierstrass was only her advisor, but he had a fatherly affection for her and saw her as his personal protege, but not as a woman – she was too intelligent to be placed in the socially defined category of a “woman.”

There are many other instances of misogyny affecting Sophia’s life. For example, while she was able to obtain her doctorate in mathematics and win the Brozin prize (a lofty honor), she was never able to find work beyond teaching. She, a highly intelligent woman, was seen as a novelty, never a colleague or an authority. Sophia is frustrated by this treatment, and by the way that she does not fit into society. There is a moment in the story which I find incredibly important, when Sophia is feeling particularly resentful of the way that she is treated, and she instinctively directs this malice at other women. However, she catches herself, and she is able to examine the ways in which her initial misogynistic thought process was not fair to other women. It is a long passage, but I will include it here:

“Then they had given her the Bordin Prize, they had kissed her hand and presented her with speeches and flowers in the most elegant lavishly lit rooms. But they had closed their doors when it came to giving her a job. They would no more think of that than of employing a learned chimpanzee. The wives of the great scientists preferred not to meet her, or invite her into their homes.

Wives were the watchers on the barricade, the invisible implacable army. Husbands shrugged sadly at their prohibitions but gave them their due. Men whose brains were blowing old notions apart were still in thrall to women whose heads were full of nothing but the necessity of tight corsets, calling cards, and conversations that filled your throat with a kind of perfumed fog.

She must stop this litany of resentment. The wives of Stockholm invited her into their houses, to the most important parties and intimate dinners. They praised her and showed her off. They welcomed her child. She might have been an oddity there, but she was an oddity that they approved of. Something like a multilingual parrot or those prodigies who could tell you without hesitation or apparent reflection that a certain date in the fourteenth century fell on a Tuesday.

No, that was not fair. They had respect for what she did, and many of them believed that more women should do such things and someday they would. So why was she a little bored by them, longing for late nights and extravagant talk. Why did it bother her that they dressed either like parsons’ wives or like Gypsies?

She was in a shocking mood, and that was on account of Jaclard and Urey and the respectable woman she could not be introduced to. And her sore throat and slight shivers, surely a full-fledged cold coming on her.

At any rate she would soon be a wife herself, and the wife of a rich and clever and accomplished man into the bargain.

Later, in the present of the story, Sophia sees a woman caring for her sick child and has a moment of introspection about the position of women in society which I thought was especially insightful: “How terrible it is, Sophia thinks. How terrible it is the lot of women.” She goes on to consider the injustices that women face, and the fact that even still, most women simply have to get on with their lives, and do not have the luxury of waxing philosophical about all of it – they simply have to get by and cope in the ways that they know how. She thinks:

“And what might this woman say if Sophia told her about the new struggles, women’s battle for votes and places at the universities? She might say, But that is not as God wills. And if Sophia urged her to get rid of this God and sharpen her mind, would she not look at her-Sophia-with a certain stubborn pity, and exhaustion, and say, How then, without God, are we to get through this life?”

This story is not simply a collection of feminist observations. It is a portrait of a particular woman’s life, and it is concerned mainly with her inner world. But this is as “feminist” as it gets – to represent women’s lives accurately, to portray them as full human beings, including the ways in which their lives are impacted by patriarchal society. Alice Munro has stated that she does not consider herself to be a feminist writer, but this may be what makes her such a great one; that she does not necessarily write with an agenda, but seeks to write about womanhood honestly and without obfuscation, including the misogyny women face, the ways that it functions and the effects it can have on their lives.

Ploting the plots and the themes of Julia 1984

May 10th, 2024 by mmcurling

Sandra Newman’s book 1984 Julia brought a new plot to George Orwell’s 1984. Newman’s novel especially gave away a new plot because the point of view was different. Julia, the character that Newman’s book follows, goes on the journey of Julia finding about how in the end Big Brother is bad and she hates him, but she not only dislikes Big Brother, she is also skeptical about the brotherhood and realizes that she will not gain any freedom from either side. On her journey to save herself and be free, Julia encounters O’Brien, the man from the Ministry of Love, who tortures Winston in Orwell’s book. In Newman’s book, O’Brien does the same thing, but before he tortures Julia, he offers her a deal. The deal is her becoming part of the inner party.

No. You are Immune. That is why you are so valuable to us. You are proof against lunacy. You can safely commit the crimes of pleasure- in you, they are even healthy. That is the mark of Homo oceanicus. In time, alll people will be so. Already, all those of the Inner Party can boast of this immunity. But of course you too will be of the Inner Party in time (Newman 147).

The passage above is the lie that O’Brien tells Julia. He trickes her and calls her valuable to the party when in the end she will actually be punished for these crimes. Julia’s immunity will actually be her downfall, and once she is done spying on Winston and the other men in Records, she will soon see this downfall. Even at some point when she was doing her spying, she gave one of the men a solution to not getting caught by Love. Julia gives Ampleworth pills that he can overdose on because in the world of Big Brother, it seems kiling youself is better than getting caught by Love. The plot of being a spy has led Julia to this moment before when she talks to others who have said it is better, and even at some point she also considers taking the pills. But to no avail spying didn’t get her the freedom she wanted, Julia even gets abother slab in the face by an inner party member who talks about how O’Brien tricks people. The inner party memeber said, “…Don’t tell me- he said he’d been watching over you for seven years? You’re the healhtiest mind he has ever encountered?” (Newman, 282). This party memeber has seen the tricks O’Brien plays on people even O’Brien’s speech. Her saying it word for word makes it all the move evident that the plot of being a spy has failed and the main plot is the lose of freedom.

Julia loses her freedom because she must change her mind and be filled with inner party thoughts. She must be filled with them and not herself. You get the feeling she isn’t free at all, even after being a spy and then running away to the Brotherhood because she sees the same things happening over there. The prisoners of war are treated much like the prisoners of war in Oceania and Julia notices that she can’t tell the Brotherhood memeber her full story. Julia must again lie about what she has done. She must lie that she was a spy for Love; she must lie that her child isn’t Big Brother’s; and she must lie about how much knowledge she know about Big Brother’s party and the four ministries. So in the end the plot is not about being a spy but about the lose of freedom that happens when totalitarian government’s face each other. The plot is about what the citizens lose instead of gain.

“Fog Count” – The Meandering Nature of the Personal Essay

May 10th, 2024 by Jess Munley

Reading the essay “Fog Count” in Leslie Jamison’s The Empathy Exams felt similar to dreaming in the way it meandered. The first couple of paragraphs explain that she’s looking for quarters in a West Virginian town in order to bring them to prison, where she will visit a man named Charlie and will buy food and drinks from the prison’s vending machine for them to share. She spends time explaining who Charlie is as a person, how they met, and who he is to her. Charlie is an ultradistance runner, a former addict, a father, and much more. They met at an  extreme ultrarun, and now they’re penpals. Jamison reached out because she thought his life was interesting. Bits of Charlie’s life in prison and some of the contents of their penpal letters are sprinkled throughout, and Jamison briefly explains the crime that put Charlie in prison.

extreme ultrarun, and now they’re penpals. Jamison reached out because she thought his life was interesting. Bits of Charlie’s life in prison and some of the contents of their penpal letters are sprinkled throughout, and Jamison briefly explains the crime that put Charlie in prison.

She switches to talking about the friend she stayed with during her visit to West Virginia, and her “ramshackle house strung with Mexican fiesta flags and skirted by an apron of oddly comforting debris: a pile of old dresses, a bucket of crushed PBR cans, an empty tofu carton with its plastic flap crushed onto the dirt.” She spends a few pages on the house and the town, trying to explain their “magic”. She reveals it through tiny, seemingly inconsequential details and an anecdote about a Boy Scout troop.

Then, very suddenly, she’s back to searching for quarters, and then she’s off to the prison. The rest of the essay is told through one continuous scene, starting with driving to the prison and ending with leaving it. The reader learns more about Charlie and all about the conversation andemotions that came from her visit.

Reading through this essay felt like falling into one story and then into another and another and then back into the first. The author leads you through a maze, and when you think you’ve reached the middle you find yourself at the start again, but with more knowledge than before. It makes it a very compelling story.

This one doesn’t directly mention Jamison’s exploration of empathy, but it’s clear that she’s thinking about it. Visiting hours end at 3pm, and Jamison is very aware of that fact as that time approaches.

“Three o’clock is just another hour in the day but it is also these things: the difference between me and Charlie, between our clothes and the dinners we’ll eat that night, between the number of people we’ll touch in the next week, between those liberties the state has deemed appropriate for his body and for mine. … Three o’clock is when one of us goes, the other one stays. Three o’clock is the end of the fantasy that his world was open or that I ever entered it. When the truth is we never occupied the same space. A space isn’t the same for a person who has chosen to be there and a person who hasn’t.”

There isn’t quite a guilt present, but there’s some form of Jamison feeling for Charlie. She writes about running in one of her letters, and questions the decision. She is wary of feeling like she’s bragging about the life she gets to live and the life he doesn’t. Even here, she recognizes that she was only ever a brief visitor, someone who could never understand the kind of life he is restricted to, and she does her best to empathize with it.

Acceptance

May 9th, 2024 by MJ

Every Heart a Doorway by Seanan McGuire grapples with the idea of what it feels like to no longer belong to the world you originally came from. Belonging and trying to find your place in all of this are at the heart of the novel. As well examining the true lengths people will go to in an attempt to achieve what they want.

But at the heart of this is acceptance. That is why Eleanor West built her school, to help her students find acceptance and move on to try and find a place they need. Most of the students aren’t at that point of acceptance that they may never see their true world again. Sumi and Kade are some of the few who accept it. While they don’t like it, they are practical in fact (Kade doesn’t even want to go back as he was kicked out for transphobic fae rules). But aside from them and Jack, most of the students cannot reach that acceptance.

Lorelei, one of the students who struggled the most with accepting that she may never find her door. She and her friends accuse others of the murders as they didn’t go to “good, respectable words of moonbeams, rainbows, and unicorn tears” and make transphobic comments to Kade. But Lorelei ends up dead, having died because she went off alone looking for her door when the students were specifically told to be safe and travel in groups. Her inability to find acceptance both literally killed her.

Jill, Jack’s twin sister couldn’t accept that her door was closed for her. She was willing to kill and mutilate to go back, uncaring for the word and the dead.

“Jill was the one Dr. Bleak locked the door against, not me. I’ve always been welcome at home, if I was willing to leave her behind… or change her” (McGurie, 164).

Jack had accepted as long as she had her sister, she couldn’t go back. So stabbing her murderess twin to then later resurrect her was the way she could get her win-win.

Nancy goes on a journey of acceptance as she learns to at least tolerate back to her contemporary world. A

“You’re nobody’s rainbow.

You’re nobody’s princess.

You’re nobody’s doorway but your own, and the only one who gets to tell you how your story ends is you” (McGuire, 168).

This note touches Nancy, and she truly accepts that while she may never find her door, she decides her fate. Not her parents, not any world, not her door. Hers and hers alone. Which exactly what Nancy needs to find her door to the Land of the Dead. I believe this is what the Lord of the Dead meant by when he told her she had to be sure before staying there. Once she took her fate into her own hands, accept what life had for her, the door would find her again.

Revisiting “The Empathy Exams”

May 9th, 2024 by Jess Munley

The first essay in Leslie Jamison’s The Empathy Exams is titled the same as the book. It introduces Jamison’s job as a medical actor, someone who pretends to be sick in order to train medical students on recognizing and diagnosing ailments. Jamison describes the detailed scripts that actors are given to memorize, that include details like age, hometown, symptoms, and fears. The scripts tell you what to reveal and when to reveal it to the students, or perhaps tell you what you know but can’t reveal. They’re formatted with sections for the character’s (patient’s) name, case summary, medications, and medical history.

For a few pages, Jamison sticks to discussing the job and the roles she plays in it, such as a woman named Stephanie Phillips who has inexplicable seizures. After each scene, she fills out an evaluation of the students’ thoroughness. “Checklist item 31,” she writes, “is generally acknowledged as the most important category: ‘Voiced empathy for my situation/problem.’” From there, she discusses empathy as an idea.

“Empathy isn’t just remembering to say that must be really hard—it’s figuring out how to bring difficulty into the light so it can be seen at all. Empathy isn’t just listening, it’s asking the questions whose answers need to be listened to. Empathy requires inquiry as much as imagination. Empathy requires you knowing you know nothing. Empathy means acknowledging a horizon of context that extends perpetually beyond what you can see: an old woman’s gonorrhea is connected to her guilt is connected to her marriage is connected to her children is connected to the days when she was a child.”

That last bit feels especially important in a medical setting. These students don’t know their patients’ histories or backgrounds beyond what they’re told. Starting the process of helping them should be done with an acknowledgement that there are reasons behind the ailments that they don’t understand, and might not ever understand completely.

After exploring the meaning and origin of the word empathy, Jamison discusses medical struggles of her own, through the lens of another character. Using this form allows her to examine her own experience through a different perspective. She presents a character who is seeking an abortion, and has an irregular heartbeat. The character’s mother wants her to bring up the heart condition in case it is relevant, but the character doesn’t want to talk about it. Even when Jamison expands on her history with her boyfriend, and the abortion, and the empathy she wants her boyfriend to express, she doesn’t expand much on her heart, at least until later.

Empathy as an idea is present even when it’s not explicit. This is true for all of the essays in this book. This essay outwardly discusses empathy more than the others, but it still has moments for empathy to hide in. After expressing that she wished her boyfriend would be more readily empathetic towards her needing to have an abortion, she writes about an evening before the procedure.

“That night we roasted vegetables and ate them at my kitchen table. Weeks before, I’d covered that table with citrus fruits and fed our friends pills made from berries that made everything sweet: grapefruit tasted like candy, beer like chocolate, Shiraz like Manischewitz—everything, actually, tasted a little like Manischewitz. Which is to say: that kitchen held the ghosts of countless days that felt easier than the one we were living now. We drank wine, and I think—I know—I drank a lot. It sickened me to think I was doing something harmful to the fetus because that meant thinking of the fetus as harmable, which made it feel more alive, which made me feel more selfish, woozy with cheap Cabernet and spoiling for a fight.”

She’s empathizing with something that can’t feel anything yet, much less appreciate her empathy. That’s part of empathy, though—sometimes it can’t help but show up, even when it makes things harder for yourself. We suffer a little ourselves in an attempt to understand others’ sufferings and put them at ease. It’s a complicated, sometimes painful process that ultimately, hopefully, makes the world an easier place to live in.

The Ending of Julia: Two Sides of The Same Coin

May 9th, 2024 by Emma Alexander

Sandra Newman’s Julia introduced many aspects to the story of 1984, but what really interested me the most was Part 3. Here we as the reader were thrust into the unknown, beyond the confines of the original story. Beyond having a conversation with Winston after she is released from The Ministry of Love, Julia is able to venture past the confines of Airstrip One. There she escapes the grasp of Big Brother and finds herself in the company of the Brotherhood. They marvel at her ability to survive torture and escape, and tell her of how they have taken over the Crystal Palace and captured Big Brother.

Sandra Newman’s Julia introduced many aspects to the story of 1984, but what really interested me the most was Part 3. Here we as the reader were thrust into the unknown, beyond the confines of the original story. Beyond having a conversation with Winston after she is released from The Ministry of Love, Julia is able to venture past the confines of Airstrip One. There she escapes the grasp of Big Brother and finds herself in the company of the Brotherhood. They marvel at her ability to survive torture and escape, and tell her of how they have taken over the Crystal Palace and captured Big Brother.

Julia is enamored with all that this group has to offer, however, she notices several things that bother her. Past all of the nicer clothes, special baths, and tasty wine, there are elements that feel very similar to life living under Big Brother. The Brotherhood’s treatment of their prisoners of war is no more humane that the treatment of those at the Ministry of Love:

“Most were boys, and some were no more than thirteen. All had the afflicted look of long malnourishment. Their postures were almost comically woebegone; they hung their heads and hugged themselves in misery” (Newman 479).

However, this is not the thing that causes Julia to panic. Instead, as she is giving her personal statements, she is shocked to hear the questions that O’Brien had mentioned:

“With a little shock, she realized what the questions were. It was the list of crimes O’Brien had said truth-followers would happily commit—the list he’d had Winston Smith agree to, when pretending to recruit him to the Brotherhood” (Newman 511).

Suddenly Julia, along with the audience, are doubtful of the Brotherhood, even though we are told that these questions should not be taken seriously. This is made even more apparent when Julia does not answer yes to one of the questions, and the person interviewing her becomes troubled with her response. Once again, she must resort to lying to survive:

“She didn’t have the freedom to think of what was right. She must do what was safe. It was as Ampleforth had said: one had no choice, one must only live through it as if one had” (Newman 513).

The society under Big Brother and the Brotherhood are two sides of the same coin: one only appears to be better than the other. Even though she had escaped to freedom, Julia is still not fully free to be open about her opinions or her actions. Newman’s Julia reminds us that no matter the intention, there is still potential for things to not be as they seem; there is an illusion of choice.

Treatment of Women In Julia

May 9th, 2024 by Emma Alexander

Sandra Newman’s Julia looks at the world in George Orwell’s1984 through the perspective of Julia. By exploring her story, the audience is able to learn so much more about the expectations of women in Big Brother’s dystopian society. Though it is mentioned in the original story, Artsem (or artificial insemination) is described in Julia to be an essential part in women’s lives. It aims to negate the need for sex altogether, offering an option for women to remain ‘pure’ while still being able to reproduce and keep the population from dipping. Women who become pregnant through Artsem also get more benefits:

“‘She could be getting better rations now, and looking forward to time in medsec, with her feet up and tea being brought by nurses. Oh, it’s jolly work, having a baby…And she’d still be a virgin! Think of that’” (Newman 39).

That being said, a woman’s body is only so useful as long it is serving the Party. This is in part why O’Brien has Julia work with him to condemn men such as Winston, and later casts her aside. The only thing that helps protect Julia in the Ministry of Love is the child she carries, which is potentially the child of Big Brother, according to the distributors of Artsem. She only serves as a means to an end, which is something deep down she already knows, but realizes too late:

“‘No, you’re a toothpick, a tissue—a thing that gets used once and thrown in the bin’” (Newman 381).

This very terrifying concept is not too far outside the realm of reality, and this book does an excellent job of showing readers just how vivid and realistic they feel. There are many instances in which Julia’s experiences are very intense and hard to grapple with, and I found myself processing them along with her.

Cultivizing a Cult: Big Brother and the Party

May 8th, 2024 by mmcurling

Reading both books, 1984 and 1984 Julia, one can sumerise that the gorvernment Big Brother can be seen not only as government enity but a religious cult. Big Brother can be seen as a religious figure within a cult because the praise of Big Brother shows the omnipotent power his image holds on the people of Oceania. Especially, when both books describe the slogan that says ‘Big Brother is Watching You.’ It is true that Big Brother- tecnically the inner party memebers- are watching you. They watch you through the telescreen, knowing everything you do. O’Brien even indicates it when he talks to both Julia and Winston but at different times. O’Brien talks to Julia first and says, “You are right. I know you more intimately than you can imagine. I have watched over you for seven years” (Newman 140). He says a similar thing to Winston in Orwell’s last part of his book. Either way, this indicates how closely the community in this religious cult is watched over. It shows that the higher ups in this community closely monitor those who have done wrong from the rules and laws Big Brother made like sexcrime, doublethink, etc.

In 1984 Julia, it demonstrates how far the cult has really gone compared to Orwell’s. In Sandra Newman’s book, she writes more about the individual sects within this Big Brother religion like Anti-Sex League. The sects have lecture about the evils of sexcrime or doublethink. Julia seems to be thrown deeper into the cult than Winston becasue she goes to most of the demonstrations and is a memebr of the Anit-Sex League. Another indication that this is a cult is the celebicy that all of them have to endear. It really hits the nail when they talk about artsem which is artificial insemenation, but it also goes further. The thing that makes this cult go even further is having a baby of Big Brother through the artsem. The talk about having Big Brother’s baby is further explained on chapter 14 of Newman’s book from pages 195-205 they call it ‘Big Future.’ One excerpt from these pages reads:

With Big Future, you are to be the true bride of Ingsoc, one of the pure vessels of a higher race…and you can wear the badge that marks you as the bearer of that greatest trust; the chance to carry Big Brother’s child (Newman 198).

This was a big revelation to the book indicating how far the party will go to have pure children from the purest of wombs much like virgin Mary, but ironiclly Julia fits the bill. This is strange because she doesn’t have pure celebicy like some people. For example, a girl from Julia’s hostel named Oceania who went through artsem but not Big Future has more of a camparison to the Virgin Mary than Julia. Still, the act of controlling even sex is very common in a cult or religious community.

Having the child of your god is a great achievement, and even Julia had feeling about it. She thought, “…She imagined fucking Big Brother in that great glass hall, where all might see” (Newmen 200). So she had similar fantasies, paralleling from what some groups or people think about God. Two people in particular think about an erotic relationship with god and they are Hildegard of Beign and John Donne. Their poems that they have written are examples of the kind of intimate relationship you can have with God. Another indication of Big Borther being the god and having ominpotent power is as follows: “Sleep is Vigilance, Six Hours For Health, Big Bother Watches over Our Peaceful Rest” (Newman 41). With these passages and descriptions, we can see the smiliarities and comparson of Big Brother being a metaphor for a cult.

We even see the metaphors of people falling for the cult or trying to run out of the cult like Winston wants to and Julia, who actually did run out. We watch Julia running from this cult after the deep seeded realization that she doesn’t love Big Brother, but hates him. She realizes she hates him and what the party stands for. She notices it after this phrase, “Twenty-seven years it had takn for her to learn what kind of smile was hidden behind the black moustache” (Newman, 330). What was behind the mousrache was a smile of vile vigor; a smile that meant power was for me and me alone; and a smile that meant that you will be crafted to my liking like a doll who had broken parts. The broken parts were the ways Julia has rebelled. It is more evident after her time at Love, where O’Brien and others tortured her. O’Brien even said something in the same lines, ” We shall squeeze you empty, and then we shall fill you with ourselves” (Newman 328). Big Brother wants to suck a person dry from thought, emotion, and self-awareness, he wants people to follow him like marionettes. But Julia does get out of this horrid metaphor of a cult, and it is illustrated at the end of Newman’s book.

In conclusion, readers may realize how much Big Brother is a representation for a cult. Big Brother’s party has to many metaphors like celebicy, praise, and faith. People seem to be falling for Big Brother everyday, especially with the constant propaganda for him. We see a rebellion starting in both books but furhter seen in Newman’s book;a rebellion from the cult that is running Oceania.

Morbid Understanding

May 8th, 2024 by MJ

Every Heart a Doorway decides to jump into murder mystery horror very quickly with the students beginning to drop like flies and accusations of who killed them begin being tossed. But throughout it all, there is a level of morbid understanding between the students. When one student mentions a dead girl’s parents should be contacted, it is quickly shut down by the morbidly logical Jack.

“If we call Lorelei’s parents, if we tell them what happened, that’s it, we’re done. Anyone who’s under eighteen gets taken home by loving parents. Half of you will be on antipsychotic drugs you don’t need before the end of the year, but hey, at least you’ll have someone to remind you to eat while you’re busy contemplating the walls. The rest of us will be out on the streets. No high school degrees, no way of coping with this world, which does not want us back” (McGuire, 105-106).

This is just accepted by almost every student when Jack says this. They have been forever changed by their worlds, allowed to become their true selves. Even the ones who didn’t get whisked off to lands of the dead or vampires are forever changed in a way that does not comply with their “born reality” anymore. This home is the only solace they have, a place where they can have support from others like them. Maybe they’ll find their door, but if not, they can find some ability to move on in a world not quite fit for them. A sense of loss and feeling unwelcome in this world binds them all, even if they don’t particularly like each other. Doesn’t matter that we have to go hide a body of your friend, school needs to not be shut down. So help out or shut up.

The morbid understanding when Jack explains why a mutilated body is of no use to her. She is in the business of reanimating the dead and you need a full body for that. With that in mind, obviously she isn’t going around killing others. While Jack isn’t particularly liked by the more fanciful land students, no one denies this. They knew deep down, that killing like this was of no use to Jack, and that if it was her killing, she’d have reanimated the body by now. So the accusations cease and they go about disposing of the body.

Kinda like one big messed up found family where you don’t particularly like some of them, but you can’t let anything bad happen to them because then it could mess it up for everyone.

Runaway

May 8th, 2024 by Grace Quintilian

In the final week of this class, I have decided to revisit the short fiction of Alice Munro. Out of everything that I have read in the course of my pursuit of this degree, Munro has had the greatest impact on me – in fact, Carrie Brown’s class “Chekhov and Munro: The Masters” was the deciding factor in my declaration of English and Creative Writing as my second major. Munro’s work is my personal ideal of a short story. This week, I have chosen to read two short stories from the collection Family Furnishings: “Too Much Happiness” and “Runaway.” In this post I will talk about “Runaway.”

“Runaway” is the story of a woman, Carla, who has found herself in an unhappy marriage to an emotionally abusive husband, Clark. With the help of her neighbor, Mrs. Jamieson, Carla is able to gather enough courage to board a bus to Toronto with the intention of finding a job there, but midway through the ride her resolve fails, and she calls Clark to come get her, telling him everything. Carla and Clark operate a riding stable together, and early on in the story we learn that their pet goat, Flora, has gone missing. This goat started off as Clark’s pet, but over time developed a special bond with Carla. After Carla’s return, Clark pays a visit to Mrs. Jamieson, who he is attempting to intimidate when Flora suddenly appears out of the mist. Clark never tells Carla this, and when he returns home Flora is not with him. Over the next few days, buzzards gather in a nearby clearing. Eventually Mrs. Jamieson writes to Carla again, apologizing for interfering in her life, and she mentions Flora’s reappearance. Carla burns the letter, and while she suspects what Clark has done, she never goes to the clearing.

“It was as if she had a murderous needle somewhere in her lungs, and by breathing carefully, she could avoid feeling it. But every once in a while she had to take a deep breath, and it was still there.”

Clark has never been physically aggressive toward Carla, as far as we know – but he could. He is a big man and quick to anger, and while he is never said to have gotten in a physical altercation with anyone, he makes a habit of intimidating others. He intimidates Mrs. Jamieson when he appears outside her home in the middle of the night, looming over her, and places his hand in her doorway to keep her from closing it. When he killed Carla’s pet and left the body for her to find, this is what he was doing. He is sweet to her after she runs away, as affectionate and “irresistible” as he was at the beginning of their relationship, because he needs to remind her of his value in her life before he will inevitably return to his true personality. He kills the goat to remind her what he is capable of. He says, in a joking manner, “if you ever run away on me again, I’ll tan your hide,” and Carla enjoys the joke. She will stay, at least for now, and ignore the reality of her situation because it is easier, and she doesn’t know how to live for herself rather than for him. When she chooses to turn back, this is what she says:

She could not picture it. Herself riding on the subway or street-car, caring for new horses, talking to new people, living among hordes of people every day who were not Clark.

A life, a place, chosen for that specific reason —that it would not contain Clark.

The strange and terrible thing coming clear to her about that world of the future, as she now pictured it, was that she would not exist there. She would only walk around, and open her mouth and speak, and do this and do that. She would not really be there. And what was strange about it was that she was doing all this, she was riding on this bus in the hope of recovering herself. As Mrs. Jamieson might say—and as she herself might with satisfaction have said-taking charge of her own life. With nobody glowering over her, nobody’s mood infecting her with misery.

But what would she care about? How would she know that she was alive?

While she was running away from him—now—Clark still kept his place in her life. But when she was finished running away, when she just went on, what would she put in his place? What else—who else—could ever be so vivid a challenge?

Carla quite literally cannot envision a life without him, that is how large his influence is. She has no life outside of him – she ran away from home and cut off all contact with her family to be with him. She has no real friends – Clark ensures this. When Carla has started to befriend Mrs. Jamieson, he becomes fixated on the idea of forcing Carla to blackmail the woman. While this never happens, by the end even she, who cared for Carla and wanted to help her be free, is gone, having moved to the city. In Mrs. Jamieson’s letter, she says that she “had made the mistake of thinking somehow that Carla’s happiness and freedom were the same thing. All she cared for was Carla’s happiness and she saw now that she – Carla – must find that in her marriage.” This reflects Carla’s feelings well. She does not feel that she can have both freedom and happiness, so she chooses happiness. When she thinks about her goat, she thinks about her free somewhere. She could go to the clearing and find the bones, thus acknowledging her reality, but she chooses to imagine that she is free. She “holds out against the temptation.”

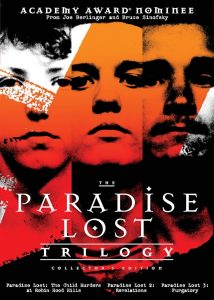

“Lost Boys” – A Test on Empathy

May 7th, 2024 by rjbillings

In Leslie Jamison’s book The Empathy Exams, there is an essay called “Lost Boys.” This essay goes over the documentary Paradise Lost: The Child Murders at Robin Hills, and what conclusions people drew who had watched it when the documentary first came out. To summarize the documentary to get a brief idea of what this essay discussed, it goes as follows: Three boys were murdered in a low-income neighborhood, and the three people that are accused of these murders are three teenage boys because they were goth and people believed they were using the murders as a ritual to summon Satan. Though the boys “confessed,” it was not a true confession. The police officer that brought them in coerced them into confessing to the murders. For years the teenage boys had been in prison for their crimes, even though they did not commit them. The documentary also goes into the families of the passed and their reaction/response to the boys being accused of the murder. Eventually, the teens, now adults, were finally released and they had a retrial that stated they were not guilty.

In Leslie Jamison’s book The Empathy Exams, there is an essay called “Lost Boys.” This essay goes over the documentary Paradise Lost: The Child Murders at Robin Hills, and what conclusions people drew who had watched it when the documentary first came out. To summarize the documentary to get a brief idea of what this essay discussed, it goes as follows: Three boys were murdered in a low-income neighborhood, and the three people that are accused of these murders are three teenage boys because they were goth and people believed they were using the murders as a ritual to summon Satan. Though the boys “confessed,” it was not a true confession. The police officer that brought them in coerced them into confessing to the murders. For years the teenage boys had been in prison for their crimes, even though they did not commit them. The documentary also goes into the families of the passed and their reaction/response to the boys being accused of the murder. Eventually, the teens, now adults, were finally released and they had a retrial that stated they were not guilty.

Because the documentary was made to show the innocence of the accused, it made the entirety of the trial and imprisonment look as if it was a witch-hunt. That everything was based on the fictitious beliefs of a police force and the people of the neighborhood that were caused by a lack of education because they lived in a low-income area which meant the public schools did not get funding for better classes. However, it also shows the parents of the three boys that were murdered and their reactions to the teens being accused of their sons’ deaths. They cursed the teens, wishing horrendous things to them as they walked out of court. The parents discussed their hatred towards them in the documentary, making the parents a villainous figure along with the police officers. As the audience first watched the documentaries, there was strong negative feedback towards the parents. A great example about how editing creates heroes and villains in an originally true, and heartbreaking, story. Jamison even discusses her disdain for the parents and the anger she felt when first watching it:

When I watched these films as a teenager, I got drunk. I wanted to feel things without thinking them through. Anger lifted me into a sentimental flurry urgent enough to match what I’d seen. These film-makers are curators of outrage; they entrust you with an injustice it hurts to hold… I got drunk and pretended to be a lawyer. I gave impassioned speeches to my hallway mirrors. This is not justice! I delivered closing arguments to no one.

Though there is truly empathy for the teens when this documentary was first shown to the public, Jamison goes against the grain of editing and asks an important question, where is the empathy for the parents? The parents of the boys who were brutally murdered are indeed horrible to the teenagers, but everyone who has watched the documentary is horrible to the parents. There is an injustice that is being served to the parents who are angry at the people they have been told killed their children. While everyone wants justice for the teens, there is no reminder that if it is not them who committed the crime, then it is someone else who got away with it. The parents need to believe it is them in order to have their anger channeled into a person rather than a faceless silhouette that will never be known. Jamison admits this, stating, “In getting mad at them [the parents], I suspect I’m doing precisely what I hate the system for doing: looking for a scapegoat.” Empathy is more than one side. Empathy is looking at the collective story, listening to the people affected by tragedies, and understanding that there are people who have reasons for being “villains” in other people’s stories. I empathize with the parents who are desperate to put a name/face to the murderer of their children and have some form of justice done to that person. However, I also empathize with the teenagers who were convenient targets for people to accuse them because there was an inability to understand their alternative lifestyles.

Weaponizing Class

May 7th, 2024 by Emma Alexander

Though it is prominent in 1984, Sandra Newman’s Julia puts more emphasis on the division between hierarchy of classes in Oceania. The Proles are shown to be fearful of messing with both Inner and Outer Party members, even going so far as to make sure that Julia is okay when someone attempts to rob her, even though they do not actually care about her. That being said, Julia understands this and shows disdain for the proles in this moment:

“They could at least have offered to punish the robber—but what nonsense to expect rightful behavior from a pack of criminals! As she walked off, she was miserably conscious of the pain that throbbed in her wrist with every step, the injury none of them had cared to notice” (Newman 102).

The hope to become a part of the higher class is also very present in this story. This is especially true for Julia, who is recruited by O’Brien to work as a spy for the Inner Party. He promises her that she can become a part of the Inner Party, in which there are many benefits, including a nicer place to live, as well as better food and amenities. Julia comes from a very poor and unfortunate background, so the promise of an even better lifestyle than the one she currently has is extremely appealing to her:

“‘But of course you too will be of the Inner Party in time.’ As he said it, his eyes subtly moved to acknowledge their surroundings. She sat up straighter, trying not to show how this arrow had found its mark. Again she was conscious of the elegance of the flat, its sweeping view, its finer air” (Newman 198).

O’Brien uses Julia’s hope to join the higher class as a way to manipulate her into doing what he wants. He could be telling the truth, but it is unclear whether this is truly genuine; he could play the part until he gets what he wants. Julia becomes more aware of this later on, though it possibly too late. The class hierarchy helps impose Big Brother’s influence even further, and keeps the people in check.

Magical Negro (Part Two)

May 7th, 2024 by ashantibrown

Today I finished Morgan Parker’s collection Magical Negro. Throughout this collection Parker was able to focus on the fetishization of black people intersecting it with media representation of black people. As stated in my previous post, the term “magical” in this context is referring to one who is unhuman or immortal. There is a long standing stereotype that black people do not feel pain or have a different pain tolerance than their white counterparts. She touches on the ways that black people are seen, treated and represented and how those effects show up at a societal level. I believe that this type of writing is what I struggle with within my own poems. I am able to write about my own experiences, it is easy and comes natural to me without a second thought, but I struggle writing pieces centered around what could be considered a generalized experience or someone else’s experience. I want to work on creating characters/personas in my poems just as Parker does.

She likes it rough. When you open her up through the mouth hole, the dumb

cunt hole. You could stomp around in there. It’s fine. She

won’t feel nothing.

That played-out scene she loves so much so she can feel

like

she got a dick:

– “Magical Negro #3: The Strong Black Woman”

I enjoy the way in which Parker is able to take deeper dives into history, mainly black history. There are things that we do not know and questions that we have that it seems that no one can answer. I envy the way that she is able to articulate these questions. It is an art, but it is also seen as so real. Again, this is something that I struggle with. I believe that before I can even begin to think of questions that I may have about my own history and the history of others doubt kicks in. I doubt if my own questions or concerns are good enough to be asked or acknowledged. There is such deep meaning to that when I ask myself why I feel that way.

Where did Harriet Tubman sleep?

Who did Harriet Tubman kiss?

What about the Africans that stayed?

Why are they hungry?

Did Fredrick Douglass’s mother

brush his hair in the morning?

Was he tender-headed and afraid?

– “Who Were Fredrick Douglass’s Cousins, and Other Quotidian Black History Facts That I Wish I Learned In School”

With this being my last blog post, I think that I can say that the whole 3 week process was very beneficial to myself and my writing. This process gave me the space to begin crafting my own voice and to find inspiration. It also opened up space for me to get to know myself more. What are the things that I can about? What are my themes? I was forced to ask myself hard questions and I was forced to examine memories or topics that were hard. I believe that I can say that I have gained confidence over these 3 weeks that I did not have before and that I can leave Sweet Briar College having a voice.

George Orwell’s 1984

May 6th, 2024 by Emma Alexander

Towards the end of the story Winston seems to hold onto hope that Golstein’s revolution is alive, and is even willing to join the cause. It offers the reader a sense of hope alongside Winston, suggesting that there may be a chance at changing the world even if it does not happen until much farther in the future. However, 1984 does not let this bit of optimism survive for very long. Winston is captured and conditioned by O’Brien, who slowly destroys Winston’s individual thought and reveals that Goldstein’s revolution may not even be real:

“’Goldstein and his heresies will live for ever. Every day, at every moment, they will be defeated, discredited, ridiculed, spat upon and yet they will always survive. This drama that I have played out with you during seven years will be played out over and over again generation after generation, always in subtler forms. Always we shall have the heretic here at our mercy, screaming with pain, broken up, contemptible—and in the end utterly penitent, saved from himself, crawling to our feet of his own accord’” (Orwell 338).

O’Brien succeeds in breaking Winston by imposing his worst fear. Up until this point, Winston has held onto Julia and kept her ‘safe’ by not giving her up. It is this moment in which he forsakes the one thing he has been clinging to, and this is what ultimately ends Winston’s resolve. He is forged to fit the image of the Party, and assimilates into society the way they want him to. This ending solidifies 1984 as a cautionary tale as to how society can become, and how it can utilize power to keep people in check. As O’Brien says, “’Always, at every moment, there will be the thrill of victory, the sensation of trampling on an enemy who is helpless. If you want a picture of the future, imagine a boot stamping on a human face—for ever’” (Orwell 337). It is a very depressing, and yet realistic message shows why we should care about the goings-on around us, and must be aware of the people who wish to be in power. They do not have others’ best interests at heart.

An Unwritten Novel

May 6th, 2024 by Grace Quintilian

In Virginia Woolf’s short story “An Unwritten Novel,” there are two parallel stories: first, there is the “real” story, which follows a passenger on a train who becomes fascinated by the older woman riding across from her. This woman seems unhappy, and instead of smoking, reading the newspaper, or in any way trying to conceal her discomfort, she simply sits and stares straight ahead of her. The two make a little small talk and the woman mentions her sister-in-law, who she calls a cow. When they reach their destination the older woman meets her son there and departs with him. The second story is the one which takes precedence over the other, and it is the story that the narrator makes up in her mind about the other woman’s life in order to explain her demeanor.

In Virginia Woolf’s short story “An Unwritten Novel,” there are two parallel stories: first, there is the “real” story, which follows a passenger on a train who becomes fascinated by the older woman riding across from her. This woman seems unhappy, and instead of smoking, reading the newspaper, or in any way trying to conceal her discomfort, she simply sits and stares straight ahead of her. The two make a little small talk and the woman mentions her sister-in-law, who she calls a cow. When they reach their destination the older woman meets her son there and departs with him. The second story is the one which takes precedence over the other, and it is the story that the narrator makes up in her mind about the other woman’s life in order to explain her demeanor.

In this story, the woman is arbitrarily named “Minnie Marsh.” She is unmarried and childless, and reluctantly traveling to stay with her sister-in-law, “Hilda.” There is a man that Minnie loves, named “James Moggridge,” a button salesman. The narrator imagines that the cause of Minnie’s somber expression is that she has committed some crime in her past which she still carries the guilt for. After some brainstorming, she determines that this crime was negligence while looking after her baby brother – she put the kettle on and left him unattended, and he tipped it over and died from the boiling water. The narrator becomes so engrossed in this version of the woman’s life that, when they reach the train station and the woman is met by a son that the narrator had not envisioned, she grows momentarily confused and upset. However, she is very quickly wrapped up in the possibilities that this son has created, and she is again flooded with wonder at the world and the people in it. She says:

“Off they go, down the road, side by side…. Well, my world’s done for! What do I stand on? What do I know? That’s not Minnie. There never was Moggridge. Who am I? Life’s bare as bone.

And yet the last look of them – he stepping from the kerb and she following him round the edge of the big building brims me with wonder – floods me anew. Mysterious figures! Mother and son. Who are you? Why do you walk down the street? Where tonight will you sleep, and then, tomorrow? Oh, how it whirls and surges – floats me afresh!”

This story effectively captures the feeling of sonder that many writers experience, and often use as inspiration for their writing. It is titled “An Unwritten Novel” because the story invented by the narrator may have later become a novel, were it not for the forced shift in perspective that she was met with at the end. There is an unwritten novel for every person alive, and this narrator is easily wrapped up in these fictional lives, even to the point that she can lose track of reality. She sees a full life behind every person she passes, and she is infinitely curious. In the very first paragraph she expresses this wonder, saying: “life’s what you see in people’s eyes; life’s what they learn, and, having learnt it, never, though they seek to hide it, cease to be aware of – what?” This is a good quality in a writer, as it marks not only a high level of creativity, but the empathy which is what makes a story feel authentic.

Morphology of the HIT: Form and Trauma

May 6th, 2024 by rjbillings

Leslie Jamison’s chapter “Morphology of THE HIT” in her book The Empathy Exams is a great example of the format working for the essay and how to navigate areas of memory that are skewed from traumatic events. The term “morphology” has two separate meanings- a biological one, and a linguistic one. The biology definition states, “the branch of biology that deals with the form of living organisms, and with relationships between their structures.” Meanwhile, the linguistic version states, “the study of the forms of words.” In this essay, it appears that Leslie is taking the biology definition as she does not say “Morphology of hit” but rather puts in all caps, “THE HIT,” and then goes into the different functions of THE HIT. I believe this is on purpose because as Leslie discusses her memory of being hit and then mugged, the entirety of the story appears to take on a separate organism that she is trying to dissect and understand. In each section of the essay, she has them numbered in Roman Numerals with titles that serve to be the “functions.”

Once the essay starts, however, its formatting begins to collapse on Jamison. When handling a traumatic event, often one of the brain’s coping mechanisms is to disassociate. By doing so, the person does not feel that the experience happened to them, but to someone that they observed. Because of disassociating, the event can often feel foreign and though it may still cause trauma to the person, the memory becomes shaky and hard to remember in order. Jamison shows this example of trauma affecting a person by purposefully messing up the numerical order of the functions at times. For example, on page 70-75 Jamison’s numbers begin to go out of sync with functions, even stating on 72 for function “III The Interdiction Is Violated” stating in the first sentence, “Now we’re out of order and we’ve hardly begun.” She then tries to continue on with the essay, but the sections are now out of order, which is causing her to loose composure as that was her only way of maintaining this memory and keeping things in order. On page 74 she reveals to the reader how deeply THE HIT affected her:

He asked me questions about what the guy looked like and I answered them badly. “he had eyebrows,” I may have said-did I say? I was waiting for adjectives to offer themselves up. But none came. The sketch on the computer screen looked nothing like the man.

While she was punched in the nose and mugged by a man, she does not remember the man, what he looked like, or giving the description of her perpetrator. She only knows that the image that the policeman drew was not what he looked like. By giving the readers this insight, Jamison is tying it back to the title of the book, The Empathy Exams. Empathy is often linked to the expression, “putting yourself in someone else’s shoes.” By creating this essay, though little is described about the man who hit her, there is enough detail that talks about how women are told not to go out at night alone, how the pain felt when her nose was hit, and how it affected her afterwards, and the embarrassment women face when a physical appearance becomes blemished because beauty is skin deep according magazines and social media.

It is not THE HIT that the essay is about, it’s about the scars that are still not healed after the face has healed, it is the culture that girls are taught at a young age to never walk alone in dark areas because of the society we live in, it is about wanting to talk about the trauma that has been experienced, but not wanting to have that be the only thing you talk about to a loved one. An important section of her letting the reader know that she wants empathy for her situation is stated on page 76, “I wanted a man to fall in love with me so he could get angry about how I’d gotten hit. I wasn’t supposed to want this. I wanted it anyway.” She did not want a man to fall in love with her, she wants the people she is closest to that now her deeply to empathize with her and to feel anger towards that experience so that she could feel justified in her own anger.

Magical Negro (Part One)

May 6th, 2024 by ashantibrown

To close out the last week of Senior Seminar I have chosen to read from Morgan Parker again, another poetry collection called Magical Negro. Just like her previous work this collection has themes of the black experience and racism, but what I found to be interesting about this collection so far are the ways that she discusses the fetishization of blackness and the ways that blackness is shown in the media. Parker does this by using experiences from her own life and also intersecting them with experiences from historical figures or celebrities. The use of Magical Negro is explained as an cinematic trope where a black characters sole purpose is to aid his/her white counterpart. This is commonly seen in roles where black people are considered sidekicks or “the best friend”. Parker is able to take this theme and combine it with real life emphasizing that black people are mortal, real, and not for entertainment purposes.

There are multiple ways in which history has been modified to present a certain outcome or belief to the masses. In some cases history has been rewritten and there are things that we are not taught. Parker points this out in her collection as well. Who are we when we speak to ourselves and who are we went we are not made to cater to whiteness? These questions presented themselves to her as she challenged herself with this collection, calling it the hardest book she has ever written. For me while reading there was a sense of urgency in her words. I do not know if it is because these are personal things that I have experienced or if that is actually the tone that she is going for in some of her poems. Either way there are emotions here that are uncovered because she is able to put these experiences into words the way others cannot.

The history of black people, after Jean-Michel Basquiat.

The history of black people: an allegory for

Denzel Washington’s continuous battle with various

forms of transportation.

The history of black people: a black feminist reading of

Cinderella starring Whitney Houston and Brandy.

– “The History of Black People”

When discussing the fetishization of the black experience Parker puts into perspective what is considered acceptable and what is considered unacceptable. It is acceptable to want black people to perform or to entertain. She uses examples of Gladys Knight, Diana Ross, Denzel Washington, Bernie Mac, and others. It is interesting because even though they represent what is considered acceptable and are of a higher status, they are still discriminated against harshly, so even then it is not enough. I believe that her poem “Let’s Get Some Better Angels at This Party” demonstrates what is considered to be unacceptable. It makes me sad to even think that. The fetishization of the black experience and black people runs deep, but it is not enough to save us.

Michael Brown, 18, due to be buried on Monday, was no angel.

– The New York Times

You always thought angels lived

in the dark. You didn’t sleep.

Appeared at the foot of Mom’s bed

covered in Nana’s perfume. You saw

and kept seeing. You let them

make a crescent of your spine.

The same thing over and over.

You don’t trust air. You call the ghosts

the angels your kin.

There is one who looks like your brother.

– “Let’s Get Some Better Angels at This Party”

Comparing Characteristics

May 5th, 2024 by mmcurling

1984 Julia by Sandra Newman is a retelling of the famous novel 1984, but from the view point of Julia, Winston Smith’s lover. In this book, we get more detail about life outside the outer party. Newman’s story has more explaination about the life of the proles than Orwell’s book because we see Julia having regular interactions with the proles. We are also introduced to the way Julia saw Winston Smith. Julia knew Smith as ‘Old Misery’ because of the way he thought about oldthink or the old ways before Big Brother, and other people called him the same thing. The description of Winston Smith was different in Orwell’s book because in his book he justified the miserable character Winston was but this book did the opposite. Winston’s misearble character wasn’t justified, he was more or less tormented by Syme for his unsavory nature. Since there was a change of how Winston was described, there was a change of how Julia was described. I am going to look at the similarities and differences of Julia’s character from 1984 and 1984 Julia.

As we have seen Winston’s character isn’t a justifiable one in Newman’s book. To her, he is a sad, gloomy man who elobes around with a sour face. Julia on the other hand is still a free spirited person in nature but she also is still cautious of what she does. If she needs to she is also willing to pull someone else under so she won’t get in trouble. We see her do it when she uses the note Vicky gives her to give to Winston. Julia does this because she knows that people wouldn’t be able to pin the note on her if they found it. The note wasn’t in her hand writing. Since she worked at the Minitry of Truth’s fiction department, she knew that her handwriting has been passed around. This meant that the note wouldn’t be pinned on her because people knew her handwriting. The note wasn’t the only thing that she has done to get out of trouble. Julia has lied and before even before giving the note to Winston. Her character can be coined a liar which she was described briefly in Orwell’s book but it didn’t explain well enough as to why her charactr lied. In Newman’s book we see the reason of why she would lie. Julia lies to, as said before, get out of toruble from the thought police. Readers even realize she is more knowledgeable about the world than Winston Smith. Her knowledge about the world is what has helped her stay alive. The explanation of what Julia knows is found on page 36 and it is as follows:

As a child of the SAZ, Julia has been raised with the lore of police interrrogations. She knew you didn’t name names if you could help it. It was as fatal to accuse those with protection as it was to defend those who had none. You must also never let the patrols draw you onto other subjects. If they asked about anything other than the incident, you talked about the incident, playing a part of a simpleton who couldn’t keep up.

This gave Julia a great advantage in her character development than Wiston’s character. We see that in 1984 Winston has had trouble rememebering his past but Julia has remebered her past. Newman writes about how Julia knows that her family was party members that eventually rebeled. She knew that once her family became enemies of Big Brother they were sent to the Semi-Autonomy Zones to work as laborers who were worked to the bone. She also knew that she could use her femine figure to get what she wanted or needed but it came at a cost. The cost was the lost of her virginity to a man who used her.

Gerber was on her, pressing and groping, a thing that could still give her pleasure, but now the pleasure was malign. He put his hand over her throat as he somtimes did… She found herslef floating on the ceiling, looking down at the wriggling, obscene figures. She thought, That girl is starving, and found it funnier than anything in the world. When she thought: But the man will die before her… This memory was warse than the memory of the hangings (Newman, 162).

At this point in Julia’s childhood. she found out the disgusting nature hunger and being opressed can get you. She was already sometimes disgusted at going to Gerber, but she felt there was nothing else to do. She knew that when she listened to Gerber’s problems, she felt power but it was short lived because of the quotas. “When he was allocating for the quotas to his farm, he asked Julia for advice…(Newman 158). So Julia was the one who helped make the quotas that turned out to be too high for anyone to meet and meant less for the people making them. This gave Julia a guilty concious and she has said she lived in fear her neighbors would find out she was responsible. The long passage above represents Julia disgust of not jut men but of what the world had to offer. She knew men would die first but the way men were in control was sad. Julia still had to use her femine ways once she got to the outer party.

The hardships Julia endeared resulted in her becoming a smart quick witted woman who dances around the poles instead of directly on them by ironically danicing on them. I am saying that with her witty nature she is smart enought to find looppoles in the society Big Brother has made. These looppoles are what has kept her alive and away from the Thought Police. Even later in the book at the end of part one and the begninng of part two we can note that her looppoles are what has made her into a spy who will look more into Winston’s behavior. This is very different from Orwell’s rendition of Julia who is a free spirit but not a spy who is quick witted but someone who does what they want based on how they feel. Julia’s character in Orwell’s book represent the emotuional freedom from Big Brother not the political freedom like Winston. In Newman’s book, Julia can be seen as both a represenation of emotinal freedom and political freedom because Julia created looppoles meaning she knows how the political system works and does things that she feels she would like to do like buy inner party goods on the black market.

To conclude, one can see that there are many differences between Julia’s character in 1984 and 1984 Julia. The easiest thing to note is that since 1984 Julia is about Julia’s perspective, it would mean that we would get more information on her character. Another thing to note is that since we are getting her perspective instead of what Winston thinks of her, we can see that she is actually more caring than mentioned in Orwell’s book. Julia isn’t someone who doesn’t care about the past, she does care about the past but she would also like to keep it in the past. Julia wants to move on from what has happened in the past and she does it by having her emitonal rebellions and wild eroticism which are there in Orwell but not as important as Winston’s life. So there may be similarities between Orwell’s book and Newman’s but there are way more differencs, and I have only scratched the surface.

Imperfect Empathy in The Empathy Exams

May 4th, 2024 by Jess Munley

Empathy is defined as the ability to understand and share the feelings of another. But does that understanding count if you don’t believe the reason for someone’s pain is the thing they say it is? Can you feel true empathy if you secretly doubt the person you are empathizing with? Chapter two of Leslie Jamison’s The Empathy Exams, “Devil’s Bait” discusses Jamison’s experience at a conference for people with Morgellons disease. The disease itself has been contested by doctors, many of whom claim it is not a physical disease but rather an affliction of the mind. As Jamison meets victims of Morgellons, she is careful to listen to their stories without confirming her belief in them.

Morgellons is characterized by fibers that emerge from underneath the skin, along with sores, itching, the feeling that something is moving under your skin, and other symptoms. 14,000 US families are affected, and 70% of Morgellons patients are women. Many are diagnosed with delusions of parasitosis and receive antipsychotics instead of physical treatment.

Jamison goes into detail about the symptoms and the lives of the people she meets, painting an almost horrifying reality that is true for thousands. However, she reveals to the reader that she is unconvinced about their testimonies. The first time Jamison hints at her disbelief, I was surprised.

“Rita tells me she lost her job and husband because of this disease. She tells me she hasn’t had health insurance in years. She tells me she can literally see her skin moving. Do I believe her? I nod. I tell myself I can agree with a declaration of pain without being certain I agree with the declaration of its cause.”

I expected her to come around, to support what the self-proclaimed “Morgies” were saying. She never did, instead exploring how she could empathize with their pain and not the cause. I was upset by this secret, but it was hard to articulate why. Jamison was still there, listening and offering at least some understanding, which is more than many Morgies’ doctors had done. I believe that her private disbelief felt like it undermined the rest of the understanding; it turned it into something disingenuous. Perhaps I’m just the type to believe anything someone tells me, so I couldn’t imagine being faced with all of these people and all of their stories and still doubting them.

I started to wonder, would it be worse if Jamison claimed to believe them, even when she did not? She never stated her disbelief, only danced around offering confirmation. Therefore, it would not have been any kinder to offer a kind of support that she wasn’t truthfully able to give. Jamison acknowledges the different type of empathy she was offering towards the end of the chapter.

“I feel an obligation to pay homage or at least accord some reverence to these patients’ collective understanding of what makes them hurt. Maybe it’s a kind of sympathetic infection in its own right: this need to go-along-with, to nod-along-with, to support; to agree.”

And yet, she resists the urge to nod along and agree wholeheartedly. However, she shows a kind of regret at her reluctance. She ends the chapter reflecting on it.

“I went to Austin because I wanted to be a different kind of listener than the kind these patients had known: doctors winking at their residents, friends biting their lips, skeptics smiling in smug bewilderment. But wanting to be different doesn’t make you so. Paul told me his crazy-ass symptoms and I didn’t believe him. Or at least, I didn’t believe him the way he wanted to be believed. I didn’t believe there were parasites laying thousands of eggs under his skin, but I did believe he hurt like there were. Which was typical. I was typical. In writing this essay, how am I doing something he wouldn’t understand as betrayal? I want to say, I heard you. To say, I pass no verdicts. But I can’t say these things to him. So instead I say this: I think he can heal. I hope he does.”

I liked that Jamison expanded the way she did. Ironically, I felt as if I understood her better. Imperfect narrators are often the most truthful with their readers, and it’s easier to still like them if you can understand them.

Chronicle of a Death Foretold

May 2nd, 2024 by Grace Quintilian

Gabriel Garcia Marquez is one of those authors whose books come with their name printed larger than the title. In other words, his reputation precedes him. I read Marquez’s most well-known novel, 100 Years of Solitude, for the course “Varieties of the Fantastic in Fiction” two years ago. Like that novel, Marquez’s slightly more recent novella Chronicle of a Death Foretold is a nonlinear story based in an insular Columbian community, which touches on the topics of culture, scandal, and honor.

Gabriel Garcia Marquez is one of those authors whose books come with their name printed larger than the title. In other words, his reputation precedes him. I read Marquez’s most well-known novel, 100 Years of Solitude, for the course “Varieties of the Fantastic in Fiction” two years ago. Like that novel, Marquez’s slightly more recent novella Chronicle of a Death Foretold is a nonlinear story based in an insular Columbian community, which touches on the topics of culture, scandal, and honor.

The novella begins with a description of the morning that Santiago Nasar was murdered. The night before, he had attended the wedding of Bayardo San Roman, a newcomer to the town, and Angela Vicario, a local. At this time, Santiago Nasar had no idea that only a few hours after the wedding Bayardo San Roman had returned his bride to her parents’ house in disgrace, having learned that she was not a virgin, and that Angela Vicario had accused Santiago Nasar of being her former lover, and that her two brothers had resolved to murder him in order to restore their sister’s honor. He also did not know that all morning the Vicario brothers had been going around town openly carrying butchers’ knives and announcing their plan to anyone they came across. Santiago Nasar would spend several hours in town interacting with different people, almost all of whom knew of the plot, and none of whom would either warn him or do anything else to prevent his death. By the time Santiago Nasar was finally warned, it was too late, and he was murdered on the steps of his mother’s house.